The Moral Decay of White America

To be a Black American in 2026 is to be an ambassador to a history that your countrymen desperately want to forget, but also an oracle or prophet of the country’s trajectory. We see, before just about anyone else, where the country is headed, having already lived through its worst-case scenarios. As Langston Hughes noted in 1936,

“Fascism is a new name for the terror

that the Negro has always faced in America.”

And whether it be gun violence, drug epidemics, or police brutality, that which the country inflicts on Black America on Monday always seems to infect the rest of the country on Tuesday. This leaves the Black American as a dissatisfied, Cassandra-esque figure, as we try to find grim satisfaction in the only words one can say in a political moment like this. I told you so.

The recent uproar in Minneapolis corroborates this bitter reality. On January 7th, 2026, Jonathan Ross, an agent of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, shot a white woman, 37-year-old Renee Nicole Good, in the face three times. Only a few weeks later, also in Minneapolis, ICE agents shot and killed a white man, Alex Jeffrey Pretti. I’ve noticed two distinct reactions to these state-sanctioned murders in the faces of my White countrymen.

The white liberals are shocked; they are always shocked. They watch the video of Jon Ross, celebrating his successful murder of a mother of three with the jubilant proclamation, “fucking bitch”, and wonder to themselves how we got here. “This is not America,” they say. “I’ve never seen anything like this.” After all, the liberal White American, for his entire historical lifespan, has nurtured a distinct short-term memory and an almost schizophrenic ability to imagine justice into spaces that it has never existed.

But even this historical naivete pales in the face of the mental condition of the white conservative. He watches a blatant murder captured in stunning quality and arrives, in desperate protest against his God-given senses, at an incoherent conclusion, or more precisely, the conclusion delivered to them by a mouthpiece of the state. Octavia Butler, the mother of Afrofuturism, warns about this wanton acceptance of fascism in her critically acclaimed Parable of the Sower. She notes, “To see and to hear even an obvious lie again, and again, and again, may be to say it, almost by reflex, then to defend it because we’ve said it, and at last to embrace it because we’ve defended it…because we cannot admit that we’ve embraced and defended an obvious lie.”

And so the American Right directs its scrutiny at Ms. Good and Mr. Pretti as opposed to the federal agents who killed them. They have channeled a great deal of mental energy and effort into a moral autopsy on the victims. Did they comply, or rather, did they comply enough? No one seems at all interested in holding the state’s agents to a similar ethical standard. It seems that it is always a citizen's duty to carry themselves in a respectable manner and to de-escalate interactions with the police, and never the opposite.

It is ironic, given my position in this country, to watch the American conservative defenestrate all his moral values and slogans. “Don’t tread on me,” they used to say. Now they insist that Ms. Good should have shown absolute deference and compliance in the face of fascism. “Shall not be infringed upon,” they said only yesterday. Today, they condemn Alex Pretti for legally carrying a firearm.

But none of this is new to Black Americans. It is not even new to white Americans, but white people have always been, perhaps more so than any other ethnic group, reticent to recognize that what happens to their neighbors is indicative of what may very well happen to them. My grandfather came to understand this reality in ‘55 when they lynched Emmett Till; I came to understand when they lynched Trayvon.

I was a fifteen-year-old boy in 2012 when George Zimmerman murdered the then seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida. I had always known, in a sort of vague sense, that I was Black, but it was at that moment, when the country proclaimed Zimmerman innocent and set him free on those Florida streets, that I understood the consequences that could so easily come with skin like this. After all, as a Black teen growing up in Atlanta, only two years and a thousand miles or so separated my experience and condition from that of Trayvon’s. It was all too easy to imagine that his fate might be my fate.

Black people in America share a unified identity and sense of struggle with every other Black face in the country, and so when a Black boy is shot in Los Angeles or Shreveport, a Black mother in Grand Rapids clutches her child all that closer to her chest.

I remember everything about that year, about that trial, but what stands out most vividly in my mind's eye was the callous manner in which the reporters pulled out their microscopes. They wanted to excavate, from that young boy’s body, a justification for his murder. Broadcasts on FOX News and local news stations showed pictures of Trayvon Martin in black and white, wearing a hoodie, as if to manufacture a mugshot; they didn’t show us his school pictures or pictures with his family.

Even at fifteen, I understood the intentions of America’s news networks and institutions. This was an intentional mass media effort to characterize Trayvon retrospectively as a criminal. After all, it is much easier to make peace with the murder of a criminal than the murder of a child, and in the mind of an American, the former identity erases that of the latter. During the trial, the defense emphasized Zimmerman’s right to protect himself, despite the fact that he, a two-hundred-and twenty-eight-pound man, had been stalking Trayvon, a minor, armed with a gun (and nearly one hundred pounds of substance in juxtaposition with his opponent).

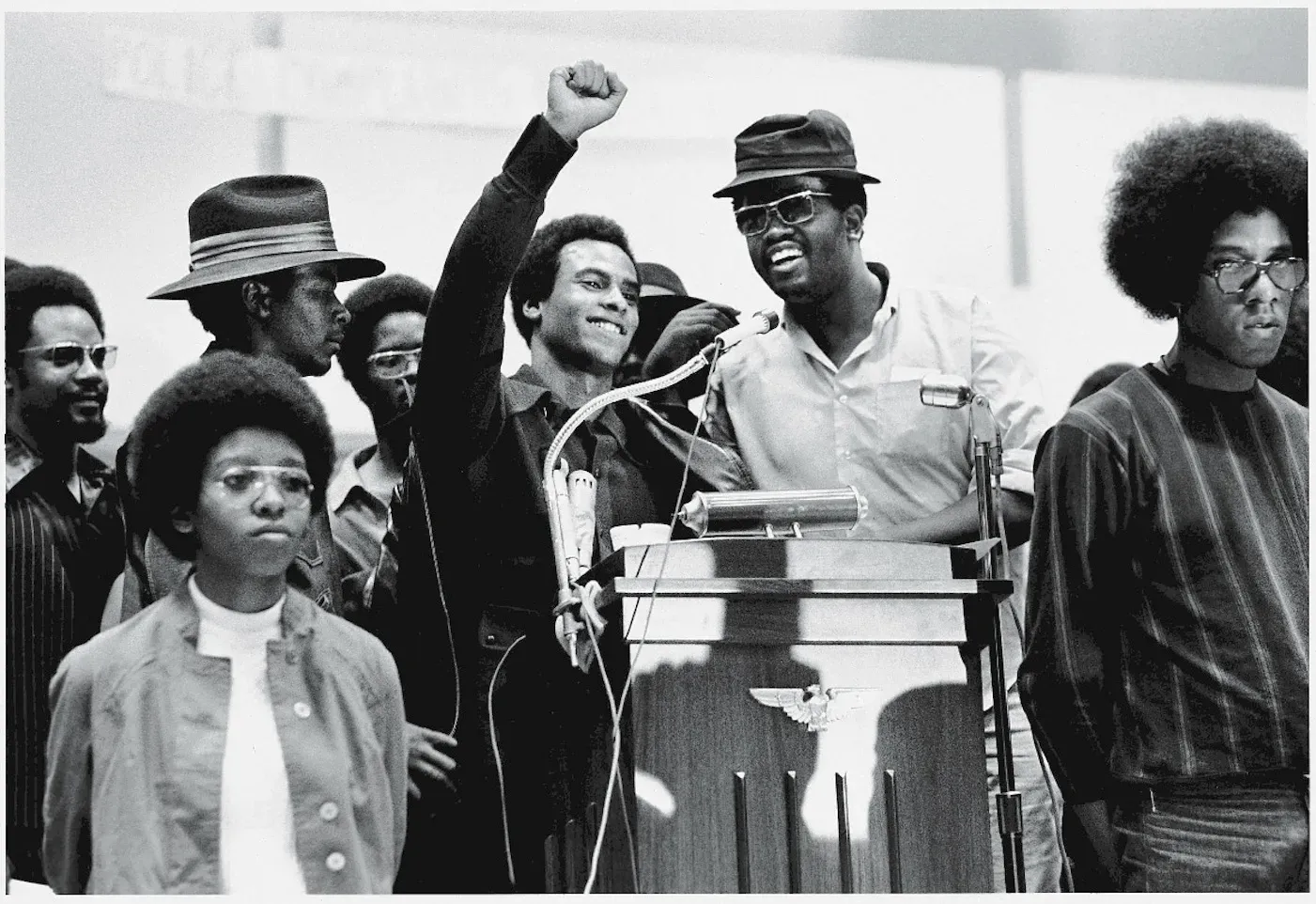

No one seemed to care or consider whether Trayvon had the right to defend himself. Then again, White America has held a consistent anxiety concerning the Black man’s right to defend himself since the days of Denmark Vesey, or more contemporarily, Huey Newton and his Panthers.

Eight years after Trayvon’s execution and the state’s endorsement of that violence, Officer Derek Chauvin infamously knelt on George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes. I will not bother to recount the event. You remember it; I remember it, and it is no coincidence that this murder also occurred in Minneapolis, nearly six years before Renee Nicole Good or Alex Pretti met that fate. And just like the media combed through Trayvon’s personal life and history for the sole effort of finding a moral blemish to justify his murder, even if that blemish was only a photo of a boy wearing a hoodie, they also made sure to inform the community of Floyd’s criminal history. They did not report on his reform efforts, his activism with local churches, or his youth mentorship programs.

Both Trayvon and George were expected to comply, to show deference to the people who killed them. I was fifteen when they killed Trayvon and twenty-two when they killed Floyd, so in one sense I can say that the first murder welcomed me to the realities of Black adolescence while the second reacquainted me with the rules of Black adulthood. And so, to the white liberal who stares at the corpses of Ms. Good and Mr. Pretti with tear-stained eyes, lamenting the simultaneous death of a more civil America, I say this to you: this is the only America I’ve ever known.

There is an old, famous James Baldwin interview filmed at Cambridge in 1965. The author of Go Tell It on the Mountain and The Fire Next Time argued against conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr.

The resolution, the topic of the debate, was whether or not the American Dream came at the expense of the American Negro. Buckley argued the negative; Baldwin argued the affirmative. I’ve watched this debate a dozen times, but there has always been one moral contention Baldwin made that eluded my understanding, not because I lacked the analytical skills to apprehend it, but because I was so bitter at the white countryman that I could not see through the fog of my own anger.

At the climax of his closing statement, Baldwin called for the moral consideration of James Gardner Clark, Jr., a police officer who employed violent methods to dispel racial protests in Selma in 1965. In one particularly gruesome instance, the officer shocked an unarmed Black woman’s breast with a cattle prod.

Baldwin comments, “...one’s got to assume he is visibly a man like me. But he doesn’t know what drives him to use the club, to menace with the gun, and to use the cattle prod. Something awful must have happened to a human being to be able to put a cattle prod against a woman’s breasts, for example. What happens to the woman is ghastly. What happens to the man who does it is in some ways much, much worse.” In the past, I thought that Baldwin was grasping for ethical straws in the darkness. How could he empathize with a man who could do something so monstrous? How could it be worse than the fate of the woman?

But now, watching America’s agents of the law barrel through white men and women with their batons and their bullets, I understand what Baldwin meant. How many Black children can the police kill before they become numb to the deaths of children in general? How many Black men can you watch die on FOX News and on YouTube and on TikTok before murder itself becomes banal?

A country so willing to dispose of its darker children, of Trayvon and George, has lost its moral backbone. It will give way to the slight push of the breeze, much less the crushing weight of fascism. It certainly lacks the necessary sturdiness to defend Alex and Nicole.

We, the Black Americans, have been told to comply, to be reverent of our killers. We have been told to be civil in our cries for justice, even with holes in our chests and blood on our teeth. We have been told this for generations. As James Baldwin once warned, “The bill is in. We’ve paid it. Now it’s your turn.”