Bad Bunny’s Halftime Show Was a Masterclass in Culture, Unity, and Hispanic Pride

Bad Bunny’s halftime show wasn’t just a performance—it was a cultural statement, delivered with precision, pride, and unapologetic joy. From its opening moments to its final image in the sky, the set unfolded as a living tribute to heritage, love, and collective celebration, rooted deeply in Puerto Rico and expanding outward to all of Latin America.

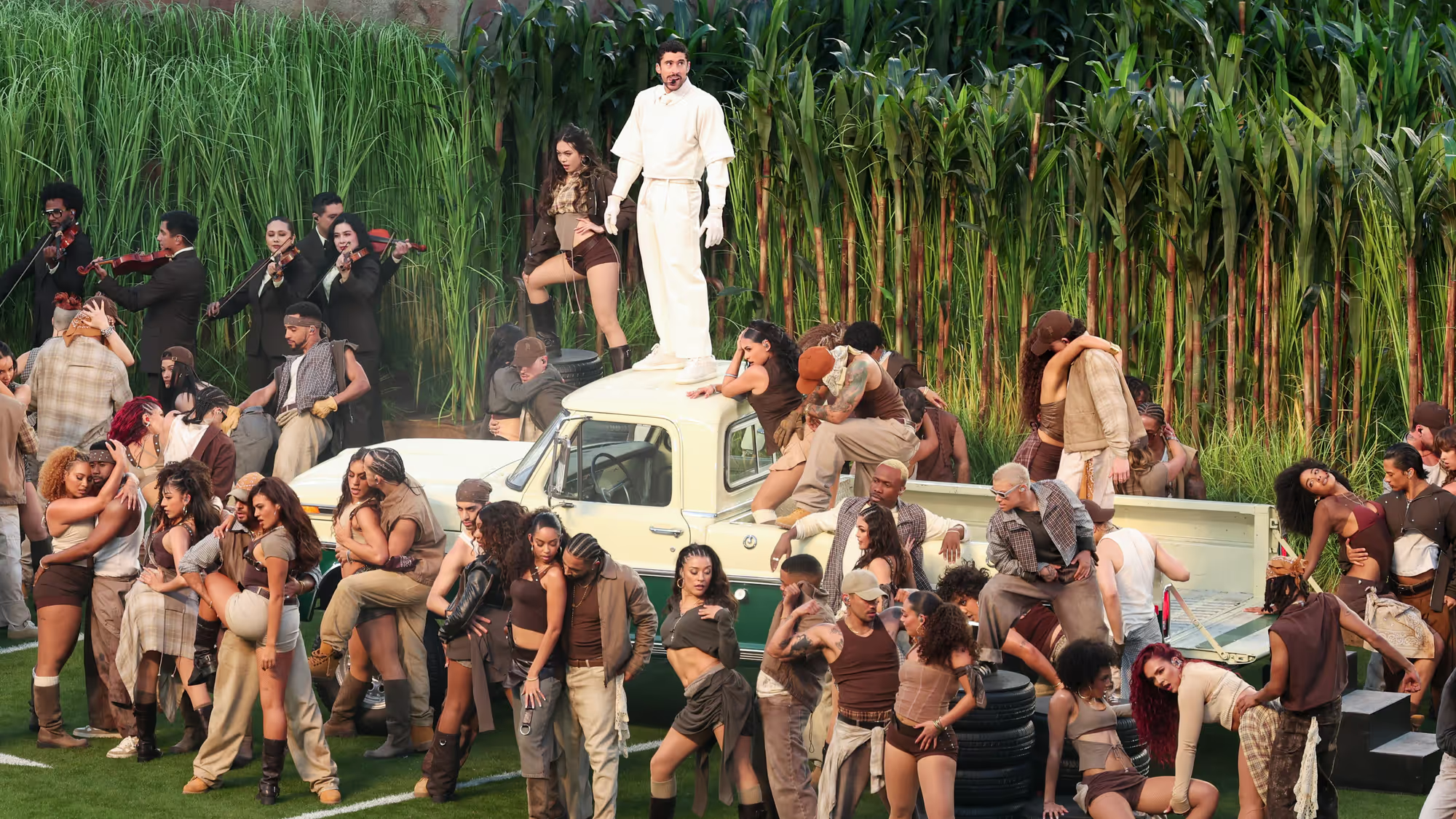

The show opened in the sugarcane fields of Puerto Rico, a deliberate and loaded visual choice. Cane fields are not simply agricultural backdrops; they are symbols of labor, colonization, survival, and generational endurance. As the performance transitioned from the fields to the football stadium—complete with cane-field props and imagery reminiscent of sharecroppers—the message was unmistakable: this culture did not arrive here by accident. It was built, worked, and carried forward.

What made the moment even more powerful was Bad Bunny’s refusal to translate himself for the occasion. The entire performance was delivered in Spanish—his native tongue—underscoring Puerto Rico’s complex identity as a U.S. territory with its own language, history, and cultural sovereignty. It was not a concession; it was a declaration.

Puerto Rico’s history is one of resilience shaped by colonization and cultural preservation. Originally inhabited by the Taíno people, the island was colonized by Spain in 1493 and later ceded to the United States in 1898 following the Spanish-American War. Though Puerto Ricans have been U.S. citizens since 1917, the island remains a territory—its people deeply American, yet often politically and economically marginalized.

Despite this, Puerto Rican culture has thrived globally, influencing music, art, food, and fashion far beyond the island’s shores. From salsa and reggaetón to literature and activism, Puerto Rico has consistently produced voices that refuse to be ignored. Bad Bunny stands firmly in that lineage.

Born Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, Bad Bunny rose from SoundCloud beginnings to become one of the most influential artists in the world. More than a global reggaetón star, he has positioned himself as a cultural force—challenging machismo, embracing vulnerability, advocating for Puerto Rico, and redefining what Latin superstardom looks like in the 21st century.

His music, image, and performances consistently center authenticity over assimilation. That ethos was on full display during the halftime show.

Bad Bunny’s halftime performance marks a significant cultural inflection point for America—not because Latin culture is new to the mainstream, but because this moment refused to dilute itself for acceptance. On one of the most widely watched stages in the country, a Hispanic artist centered language, history, and community without apology or translation. That alone signals a shift.

For decades, American mass entertainment has welcomed multicultural influence only after it has been softened, subtitled, or reshaped to fit a narrow definition of “universal.” This performance challenged that framework. Spanish was not a stylistic flourish—it was the foundation. Puerto Rican history was not background texture—it was the opening scene. Celebration was not escapism—it was the message.

Culturally, this moment reflects an America that is no longer asking permission to exist in full. Hispanic and Latin communities are not emerging voices; they are central contributors to the nation’s cultural economy, political discourse, and artistic direction. Bad Bunny’s presence on that stage affirmed what demographics and streaming data have already proven: American culture is multilingual, multiethnic, and increasingly defined by global diasporas rather than a single dominant narrative.

Perhaps most importantly, the show reframed joy as a form of resistance. In a climate shaped by polarization and fatigue, the performance argued—visually and emotionally—that celebration, love, and cultural pride are not distractions from the American story. They are the story.

In that sense, Bad Bunny didn’t just headline a halftime show. He expanded the definition of who America sees, hears, and honors at its center.

The performance itself was electrifying and undeniably sensual, but never gratuitous. The dancers embodied the joy of outdoor family gatherings, block parties, and community celebrations—the kind that stretch from afternoon into night. At one point, the choreography even staged a short wedding ceremony and reception, a nod to communal love and shared milestones that define Latin family culture.

Guest appearances by Lady Gaga and Ricky Martin added generational and cross-cultural weight, reinforcing the show’s message of unity rather than spectacle for spectacle’s sake. The finale brought together flags representing Latin American countries, flying high as the performance expanded beyond Puerto Rico into a pan–Latin American celebration.

As the cameras panned upward, the closing image sealed the moment: a billboard reading,

“The only thing more

powerful than hate is love.”

It wasn’t subtle—and it didn’t need to be.

In an era where halftime shows often aim for mass appeal by flattening identity, Bad Bunny did the opposite. He brought history, language, sexuality, and pride to one of the world’s largest stages—and trusted the audience to meet him there.

For Lenox and Parker, the takeaway is clear: this wasn’t just an amazing halftime show. It was a reminder that culture, when honored fully and fearlessly, is the most powerful performance of all.