Against The Genocide of Children

…but our children are not ours/

nor we theirs they are future we are past

- Nikki Giovanni, Always There Are The Children, 1976

Every Christmas, after dinner, but before my younger step-siblings and cousins open their presents beneath the tree, my grandmother and I play rummikub on an old, rickety wooden table that is at least six years my senior. We each indulge in a bowl of Blue Bell vanilla ice cream during the contest, in direct rebellion against my lactose intolerance and her dietitian's prescribed suggestion. It is a tradition that stretches back to my childhood, and I hope it will continue for many years. It wasn’t always just us two; my great aunts and uncles, Maddie, Olivia, and Dewie, all used to gather around the table, but time has collected each one of them between its fingers and run off into the metaphysical distance. Eventually, time will make a memory of my grandmother as well and leave this tradition in my hands as an inheritance. Still, there is no one in my immediate line of sight, or even at the edges of my periphery, to pass the ritual onto. It ends with me.

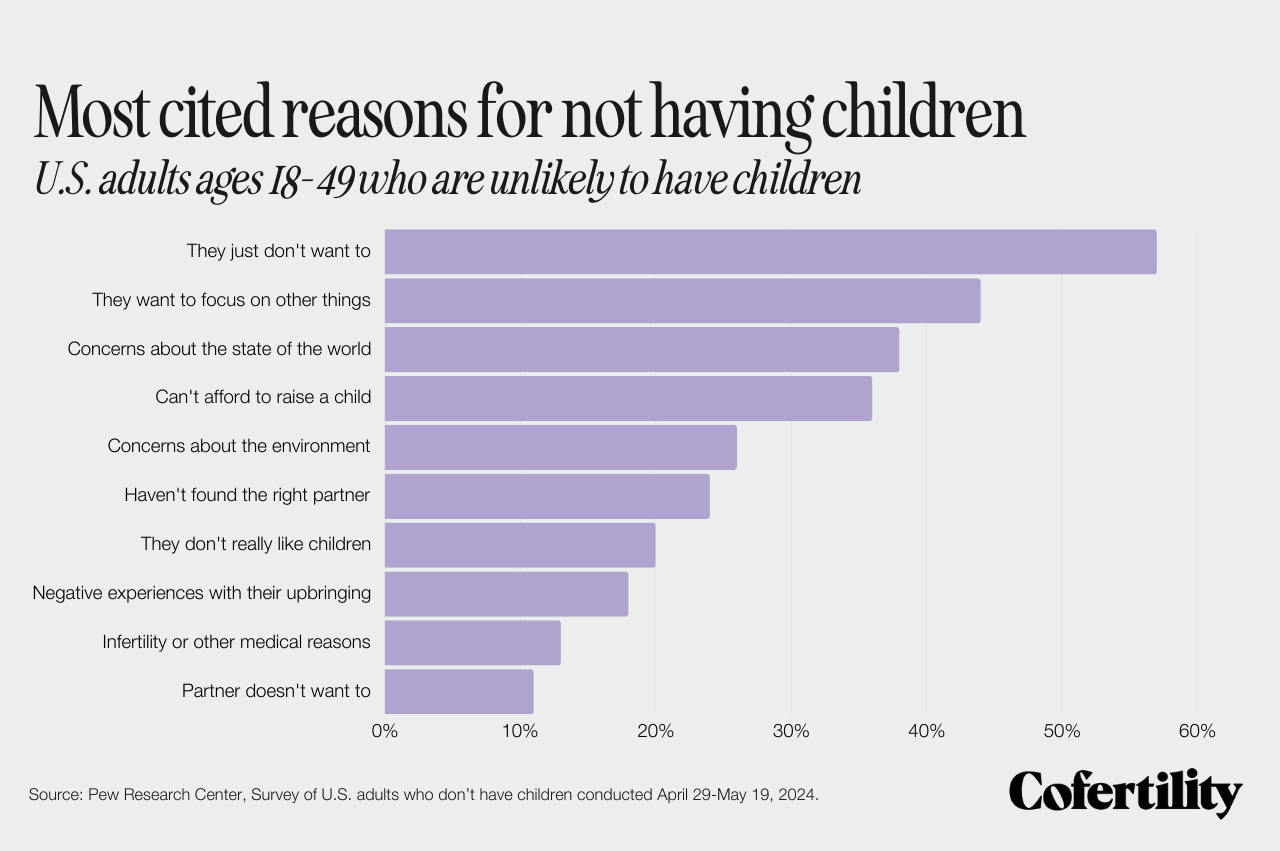

Once, after a particularly close game, my grandmother looked at me long and hard. She said, “So, you really don’t think you’ll have any children?” I paused, considered her feelings, and scooped up an overly large serving of ice cream. It melted quickly on my tongue. “I’m sure,” I said. We reset the board and played again. My grandmother is not the only one who has asked. My mother was only twenty when she had her first child, and my father was twenty-two; I am twenty-eight. As an older representative of Generation Z, I do not consider my stance as unusual. In many ways, I am just another corroborating instance of a larger generational trend. We are not having kids, a fact that continues to astound Millennials, Generation X, and, most dramatically, Baby Boomers. Recent surveys on the subject indicate that anywhere between 25% and 40% of young adults either do not want to have children in the future or are abstaining due to economic pressures.

This severe increase in antinatalism, the philosophical stance against having children, has prompted the Trump administration to consider offering stipends, a hypothetical $5,000 “baby bonus” to address childcare concerns for new mothers. Realistically, I doubt that such a relatively small stipend, even if the rumored proposal were brought to Congress as a bill, would do much to acknowledge the economic challenges of child-rearing. After all, expenses for a baby can reach up to thirty thousand dollars in the first year, depending on location and cost of living.

Further, while the Republican Party claims to care about working-class families, they have leveraged their power in a brutal campaign against government assistance for families, including SNAP, Medicaid, Head Start, and WIC. Still, there have been other recessions, much more severe ones, that did not affect fertility optimism, the enthusiasm to have children, to such a degree. After the Great Depression, for instance, fertility rates rebounded. For the Millennials, the 2008 housing crisis brought about a shift in parental timelines. Many women elected to undergo “geriatric” pregnancy in their later years as more established adults to dodge economic turmoil. However, the goal was still to establish a family at some point. For Generation Z, however, the matter isn’t a question of when, but a definitive statement: never.

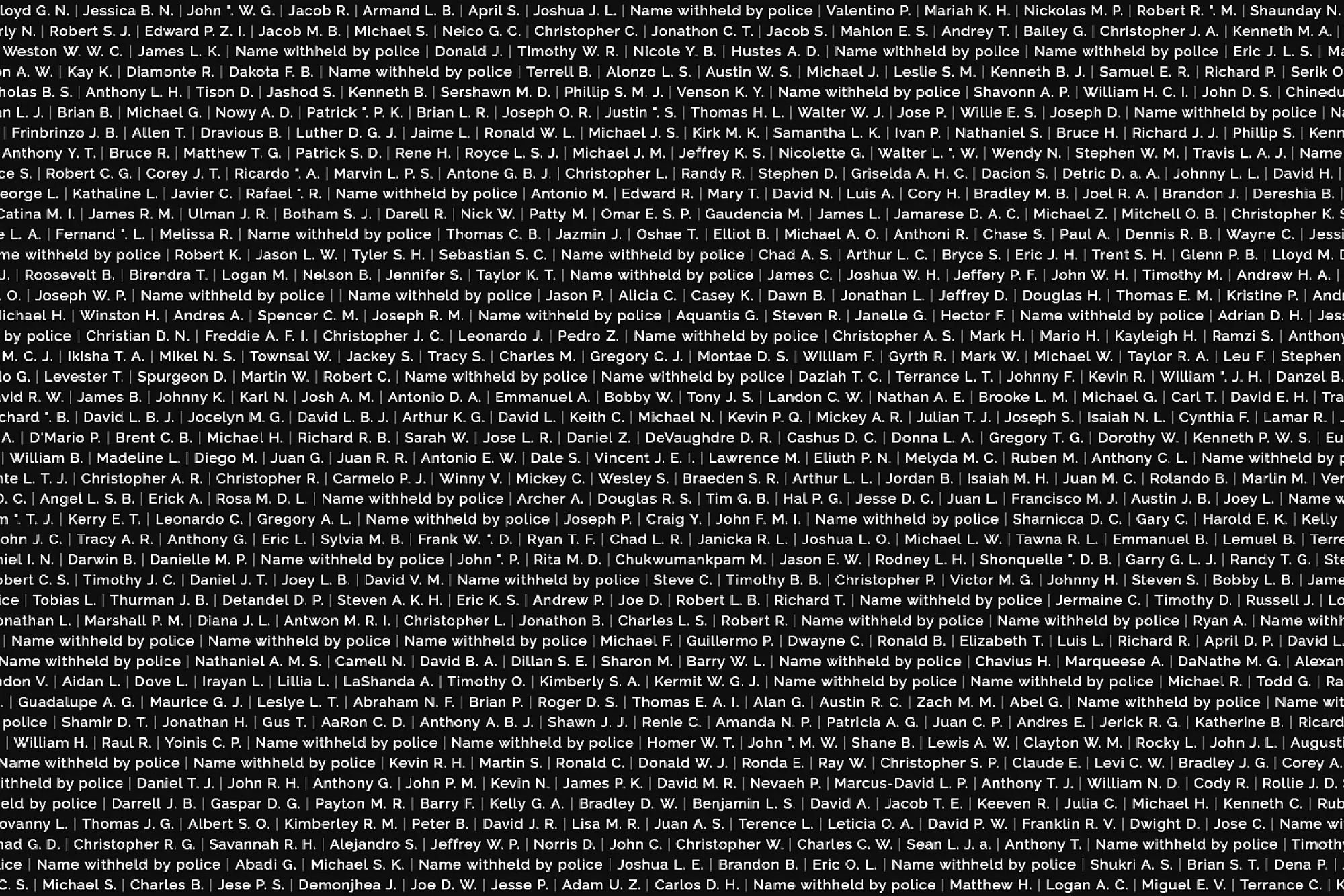

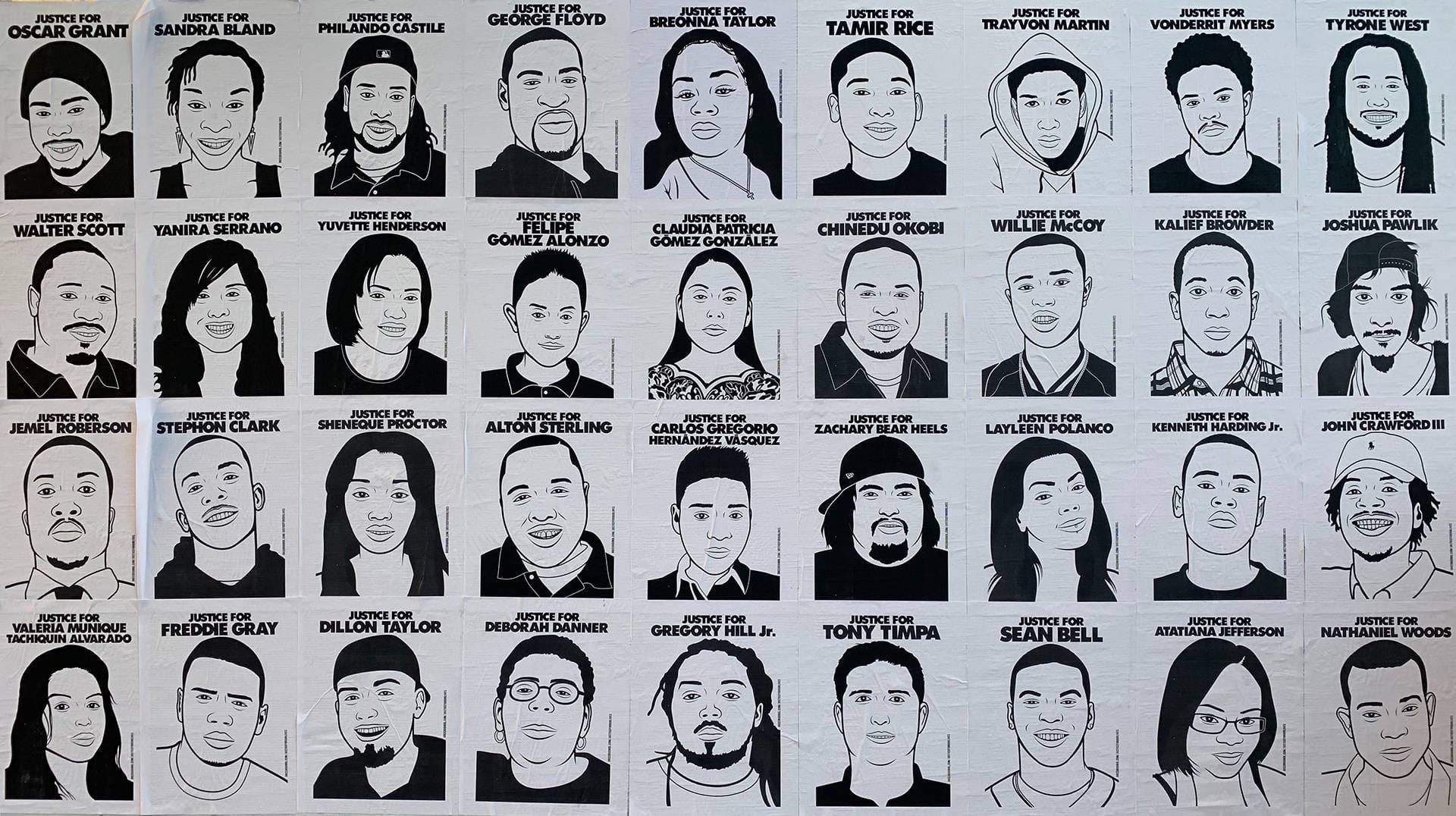

Economic realities alone fail to capture my generation’s unique ambivalence towards natalism. I am still relatively young. Still, when I look over my shoulder at the long, winding road I’ve walked to reach manhood, I am forced to reckon with the corpses of children who were run down on that road by bullets, police batons, and bombs. I look back, and I feel very, very old. To come of age with Black skin in the iPhone generation is to memorize and recite the names of Tamir Rice, Aiyana Stanley Jones, Trayvon Martin, and Laquan McDonald. You are forced to learn, through their deaths, the same violent curriculum forced onto every Black child—that the institutions of this country, the police, the courts, and the jury, are impotent, derelict, and negligent of their obligation to you. They do not see your parents as people, and therefore, at the age of seven, nine, or ten, you know that they do not see you as a child.

Only three years ago, a sixteen-year-old Black boy, Ralph Yarl, went to pick up his twin brothers from a house in his neighborhood and knocked on the wrong door. He was greeted not with correction, but with two bullets, fired through the front door. One of the bullets punched through Ralph’s skull, and the other bit through his arm. Then 86-year-old Andrew Lester saw, in the young boy, a threat worthy of capital punishment. I thank God often that Yarl survived—but when I consider the margin of error, that infinitesimally small pin upon which Ralph Yarl’s life dangled, I am filled with such gripping fear and anger that I might erupt.

I thought of Ralph, Tamir, Trayvon, and Aiyana last Christmas when my grandmother asked me about children. I thought about the conversations I had with my father after they shot Philando Castile in front of his four-year-old daughter, and the conversations with my mother after they took Mike Brown. And so I have known ever since I was old enough to know anything, that I cannot bring a Black child into this world, at least, not in America, where the stars might burn his flesh and the stripes will be lashed over his back. For a long time, I thought that this truth, that the children are not safe, was a Black truth. And it is a Black truth—but Black people are no longer alone in the struggle to preserve the lives of our children. Since 2020, America has lost slightly over 40,000 people to gun violence per year. Within that same time period, the country has endured an average of 245 school shootings per year. You can scarcely watch the news or scroll on social media without hearing about a local elementary or high school grieving the loss of its students and teachers, all the while, politicians across the political aisle do nothing but offer their thoughts (from the safety of their unaffected homes) and their prayers (to a God that I can’t imagine they actually believe in).

Two years before conservative commentator Charlie Kirk died to gun violence himself last September, he argued, “ I think it’s worth to have a cost of, unfortunately, some gun deaths every single year so that we can have the Second Amendment to protect our other God‑given rights.” However, I think there is something to be said about a man—and a country—that values his unrestricted right to weaponry over hundreds of children’s right to life. I will not argue against the notion that a person may own a gun for the sole purpose of protecting his family, but I will say earnestly that I have witnessed a great deal of families crippled by gun violence, and a scant few who have been protected; I know well the names of the children marked for death by our inalienable right to the gun, and cannot name one child at all who has been saved.

Generation Z has grown up in a time that insists children be collateral damage for the endurance of the adult status quo. Scientists warn that fossil fuels and energy consumption are draining the planet of its vitality, and that our children find themselves without easy access to potable water or fertile soil. Yet, our politicians refuse to acknowledge this existential threat. Last September, Trump stood before the United Nations and called Climate Change a “con job”. I am no scientist, but I imagine that for those who were forced to evacuate during the Los Angeles wildfires or the floods in Central Texas, the President’s comments offered no comfort. We are the iPhone generation; for our entire lives, we have looked at the world through a vast, digital window.

Martin Luther King’s famous essay, “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” argued that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

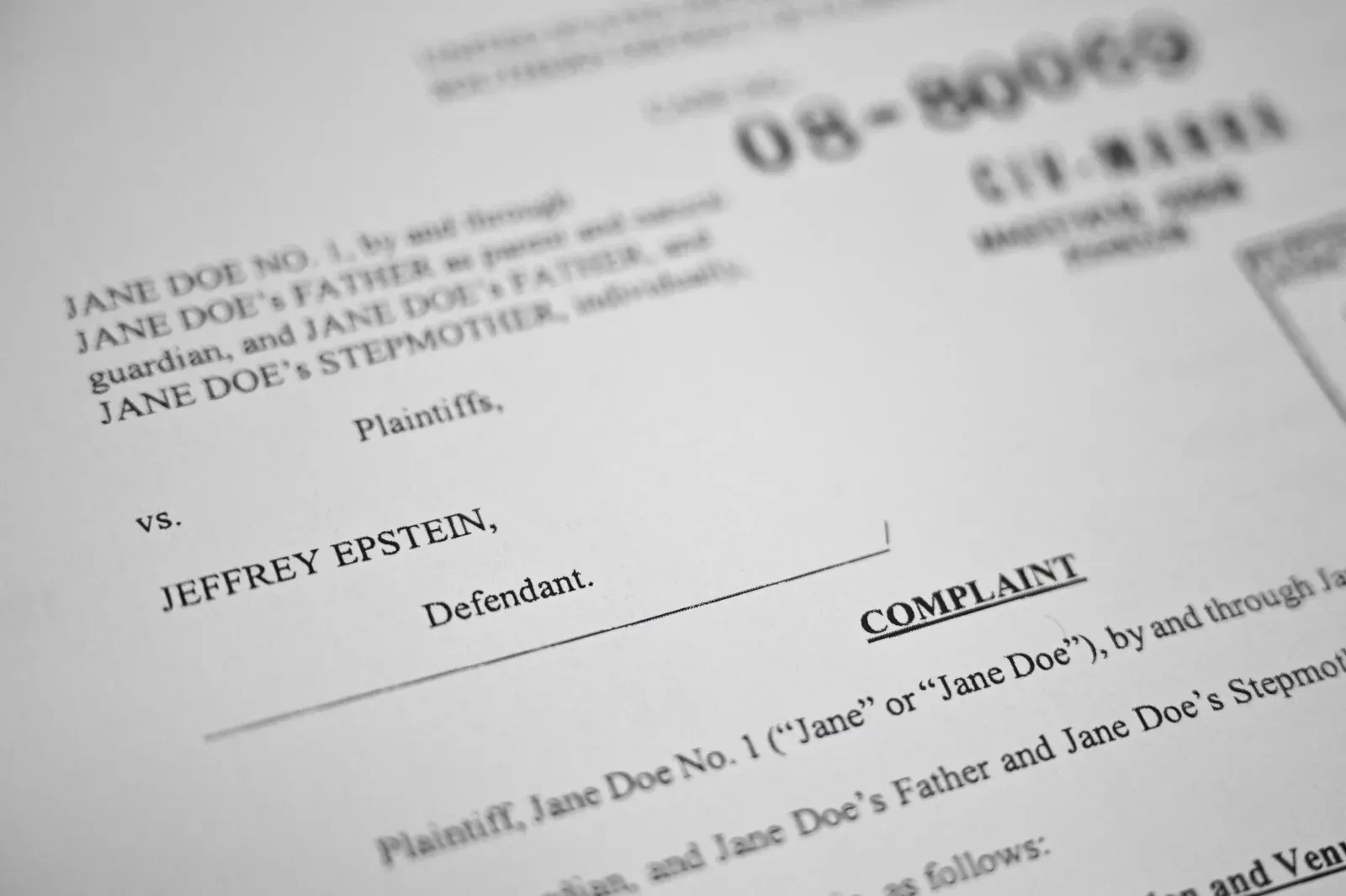

And though he wrote those words in 1963, those of us born in the digital age apprehend them more than any of our ancestors. We watched Israel carpet bomb Gaza for two long years and steal the lives of over 17,000 children on our phone screens. We tried to avert our gaze from the carnage, only to see ICE officials, dressed in masks like their Klan predecessors, terrorizing Somalian children in Minnesota and stuffing brown children in cages. We turn away from our televisions, and then there are the Epstein files on our computers—everywhere, another transgression against the world’s most vulnerable population.

I am a writer, but I am also a teacher. I am also still learning the responsibilities of adulthood and the privilege of independence. As a man without children, teaching has a vantage point, a lens into the lives of children. After all, though we all were once young, it is all too easy to forget what it was like to live without agency or self-determination. They rely on us to protect them, or at least, they are supposed to. But when you look at the Black Lives Matter protests, it is the children who occupy the front lines, standing against the police armed with nothing but picket signs and hope.

Remember back to the 2017 March for Our Lives protest, after Nikolas Cruz barreled through Parkland High School with a rifle and killed seventeen people. Who led that discussion? Whether it be Greta Thunberg arguing for climate reform at the UN or the Black Student Unions constantly pushing the police and the politicians towards equitable practices, we have created a world in which the children must protect themselves from our indecision, from our cowardice, from our immorality. From us.

And so I cannot bring a son, daughter, or child into this world to be swallowed up, not until or unless I am prepared to speak out with enough fervor in favor of a world worthy of children. I explained this to my grandmother last Christmas, over a game of Rummikub and Blue Bell ice cream. I know she hopes for a change.