Why I’m Done With Kanye West

Before I was ever critical of Kanye West, I was a real fan. Not a casual listener, or a late adopter, but a witness to his brilliance.

The first time I saw Kanye perform, was my 30th birthday weekend. He was a brand-new artist, an opening act at Philips Arena in Atlanta, back when Confessions had catapulted Usher into being the biggest thing in pop culture. The building was a frenzy—fans pushing forward, buzzing, anxious, desperate to see him take the stage. It’s safe to say the crowd was there for Usher. I was seated in the first few rows. The arena felt enormous. The energy was already electric. Then the stage went completely black. A single piano appeared.

Out walked an artist most of the crowd barely recognized although they had more than likely heard his debut single. The stage was empty except for that piano and Kanye. There weren’t any lights, pyrotechnics, theatrics or spectacle. There weren’t even any dancers or a hype man. He opened with “Through the Fire,” his reimagined version of Chaka Khan’s classic, delivered with such raw intensity that the room shifted. Later, we would learn that the man at the piano was John Legend. At the time, he was simply another unknown, supporting an artist who felt like a revelation.

Kanye followed it with “Jesus Walks.” And suddenly, tens of thousands of people who had come to see Usher realized they were standing in the presence of someone who could command an arena with nothing but conviction, clever lyricism, raw passion and belief. That night, he gained a real fan.

That moment for me was unforgettable, which is why this decision did not come quickly. It came after years of watching, listening, excusing, and finally accepting what had always been there.

There is no honest conversation about Kanye West that doesn’t begin with his talent. To deny it would be intellectually dishonest. He is one of the most gifted artists we have ever witnessed—musically, lyrically, emotionally. His production reshaped hip-hop. His vulnerability expanded it. The College Dropout didn’t simply entertain; it articulated the interior lives of middle-class Black youth who rarely saw their ambition, insecurity, faith, and hunger reflected with nuance. Kanye felt like one of ours, And that is why this is beyond difficult, it’s painful.

But talent is not a moral currency. It cannot be traded for ethics. It does not excuse harm. History has shown us repeatedly that brilliance does not and should not absolve damage.

I began my career as a writer in college, contributing to a Black publication in Oklahoma, rooted in the belief that our stories deserved to be told by us. After relocating to Atlanta, I transitioned into publicity, while continuing to write freelance for urban and indie hip-hop magazines that centered culture long before it was profitable. Later in my career, I intentionally reduced my celebrity publicist roster and accepted a role as Women’s Issues & Relationships Editor at one of the longest-running Black publications in the country.

I am proud of the work I’ve done telling our stories and celebrating our cultural heroes. Two years ago, I accepted the position of Editor-in-Chief of Lenox & Parker, a luxury and lifestyle publication committed to unapologetic Black and Brown excellence. My career history gives me the right to stand on business with the talent our community cherishes. The saying “all skinfolk ain’t kinfolk” is grounded in truth. And this is mine.

As the Editor-in-Chief of a black publication, I have reached a point where I can no longer celebrate Kanye nostalgically, conditionally, or with caveats attached.

Kanye was once one of my favorites. His presence a priority in every playlist. His grief after losing his mother felt familiar, especially to me as a Black woman. I understood what it meant for a Black man child to lose his emotional center. We gave Kanye grace because we recognized the wound before we acknowledged the pattern. As Black women do, we empathized, protected, excused and ultimately absolved his bad behavior away.

But over time, Kanye told us exactly who he was.

He told us in his music long before we were ready to listen. When he joked that success would lead a successful Black man to leave Black women behind, we laughed, danced, and overlooked the truth embedded in the punchline. Later, as his public partnerships consistently centered women outside of the culture, it became clear this was not coincidence.

Even his most celebrated “pro-Black” moments deserve reconsideration. When he interrupted Taylor Swift onstage to declare that Beyoncé deserved the award, it felt like racial solidarity. In hindsight, it reads more like alignment with power. When he declared on national television that George W. Bush didn’t like Black people, we mistook spectacle for sacrifice.

The same pattern followed him into fashion, into radio interviews, into public fallouts. His strained but publicized relationship with Virgil Abloh revealed a truth many were reluctant to say aloud: Kanye has never truly been about the culture. He has always been about Kanye.

Then came the diagnoses. Bipolar disorder became the explanation we clung to as behavior escalated. And again, the Black community, particularly Black women, did what we are conditioned to do. We contextualized. We empathized. We absorbed emotional labor.

Until he aligned himself with Donald Trump, wore a MAGA hat, declared slavery a choice, and demeaned the ancestors whose suffering made his success possible. Still, many hesitated.

Then came the Nazi rhetoric and antisemitism, coupled with attacks on the Black community and even vitriol aimed at the family he created.

The Jewish community’s response to Kanye West’s antisemitic rants carried immediate and palpable consequences. Partnerships were severed. Access was revoked. Financial ties were cut. The message was unmistakable: certain lines cannot be crossed without repercussion. It was only after those consequences were enforced that Kanye sought out Rabbi Yoshiyahu Yosef Pinto, a highly respected Israeli-Moroccan Orthodox Rabbi in New York to apologize for his random antisemitic tirades over recent years

Although I believe the intent was to, position himself as reflective and remorseful, the action signified a measured amount of respect.

No such olive branch followed his tirades against his own community. After declaring that slavery was a choice—a statement that demeaned generations of Black suffering and survival—there was no comparable atonement tour, no deliberate effort to repair the damage with Black institutions or Black media. The disparity reveals an uncomfortable truth: there are consequences for disrespecting some communities, but not for disrespecting the Black one. And until that imbalance is addressed, Kanye’s gestures of remorse will continue to feel less like accountability and more like strategy.

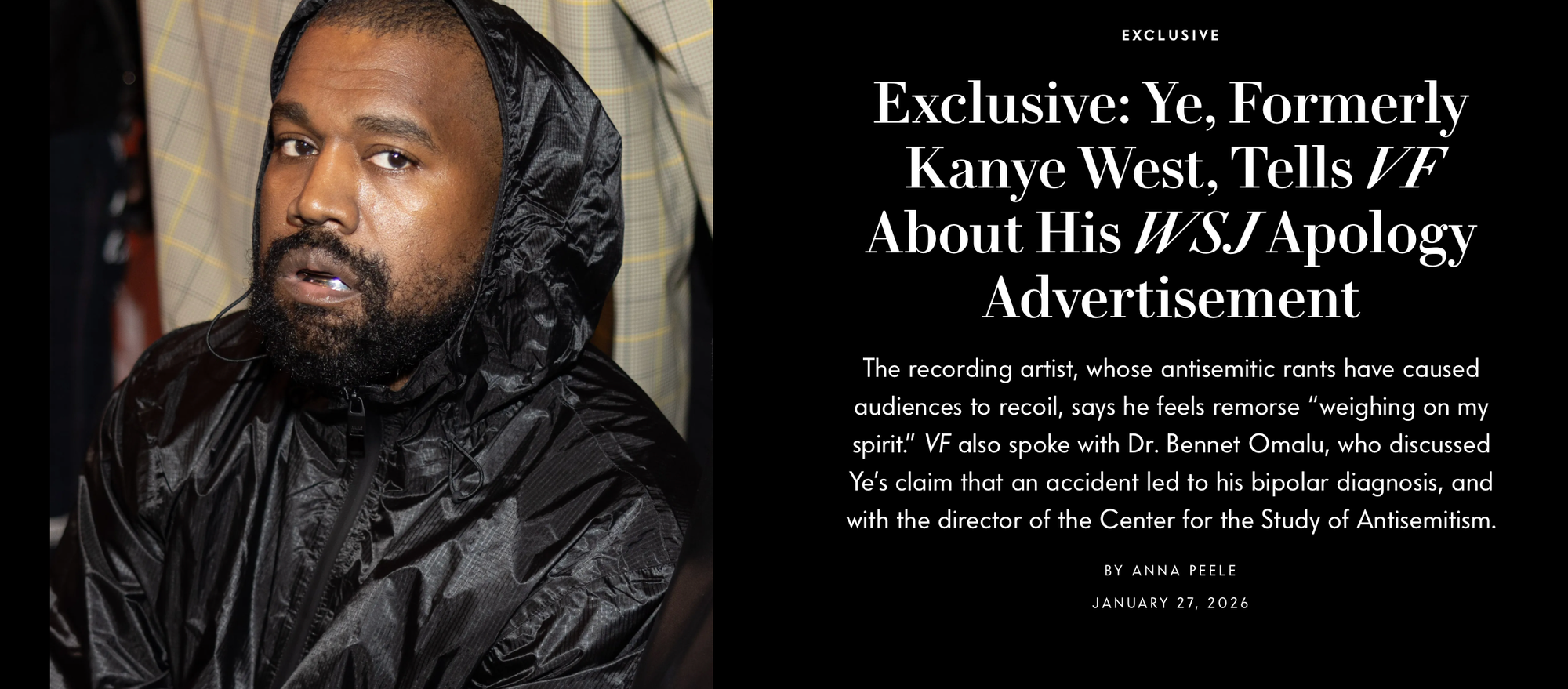

When I first saw Kanye’s apology published as a paid advertisement in The Wall Street Journal, we did not yet know an album was coming. For a moment, many people wanted to believe. I heard it in conversations. I saw it online. This feels sincere. Maybe he finally gets it. But my professional gut said otherwise.

As a former entertainment publicist, I understand strategy, timing and optics. Everything about that placement told me this was not repentance, it was positioning. The Journal is not where culture goes to be repaired. It is where reputations are stabilized and capital is reassured. At the time, I didn’t argue, I decided to wait.

Days later, when Kanye sat down with Vanity Fair, and it was confirmed that a new album was on the way, my intuition was validated. What struck me was not surprise, but the disappointment of others the hurt, the embarrassment of people who had once again extended grace only to realize they had been invited into a familiar cycle. For them, it stung, but for me it offered resolute clarity.

Black media is not a stepping stone, or a placeholder. It is not a practice run before “real” press.

Indie artists rush to Black media when they need belief, credibility, and cultural validation. We are called early, leaned on heavily, and expected to show up fully. We contextualize genius. We defend complexity. We amplify with limited resources. We build momentum long before money arrives.

Then the projects go mainstream, and suddenly the dollars migrate and the access shifts, the “exclusives” exclude us for outlets that do not prioritize our issues but profit off of our culture. In this process the loyalty from talent we claim as “ours” evaporates.

As editors, writers, and publishers, we understand business. We understand reach and scale. Many of us have learned to excuse bias and misuse as the cost of survival. We have swallowed disrespect and renamed it strategy. But with anything that exists outside of love, there is a line.

That line is crossed when Black emotion is extracted while Black institutions are bypassed.

To appeal to the Black community through the Wall Street Journal, then confirm intent through Vanity Fair—while Black media is ignored yet again—is not an oversight. It is a statement.

To me it says:

Kanye wants our forgiveness and our patronage but not our partnership.

He wants your emotional labor, not our platforms.

He wants our loyalty without accountability.

As a member of Black media, I’m done accepting that arrangement.

So I have released Kanye West.

Not quietly or privately, but publicly and intentionally

As a member of Black media—media that is consistently overlooked, undervalued, and taken advantage of by its own—I no longer recognize him as part of a community I love and celebrate.

In my eyes, he is no longer one of us.

And this time, the line holds.

Editor’s Note

At Lenox & Parker, this op-ed reflects a broader editorial stance—not a momentary reaction. Black media has long been asked to subsidize culture without being treated as cultural infrastructure. This piece marks a boundary. We will continue to celebrate Black excellence, but not at the expense of Black institutions, Black labor, or Black dignity.

A Call to Black Media

To the editors, writers, bloggers, publishers, podcasters, and cultural curators:

You are not “early press.”

You are not a courtesy stop.

You are not optional.

Our platforms and labor matter, and our boundaries should as well.

We are allowed to stop carrying those who refuse to carry us.