Jazmine Sullivan Tried to Save the Good Girls—Nicole and Channon Proved Why It’s So Hard

While reality television began dissecting modern dating with cameras and confessionals, Jazmine Sullivan issued women a quiet warning. A Girl Like Me was not a love song, nor was it a plea. It was a reckoning—a meditation on what happens when women follow every rule they were given and still find themselves waiting to be chosen in a world that no longer rewards restraint.

On Ready to Love Detroit, that warning unfolds in real time through Nicole and Channon, two women who embody what many would still describe as the gold standard of “wife material.” They are educated, accomplished, polished, and deeply intentional. They are the kind of women parents hope their sons bring home, the kind of women society assures will be rewarded for their discipline. Yet their experiences reveal a truth many good girls are reluctant to confront: virtue alone is no longer currency in the modern dating economy.

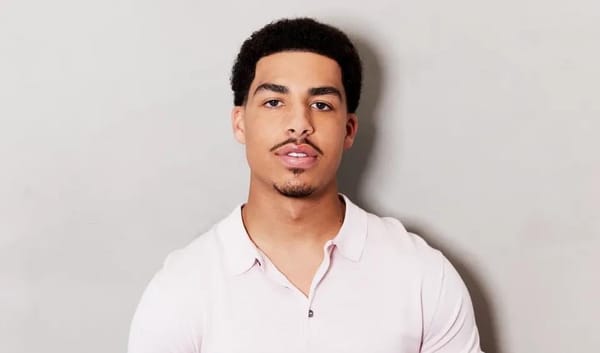

Nicole is a walking résumé of achievement. A PhD holder and former beauty queen, she represents ambition, self-control, and legacy wrapped in warmth and approachability. Her presence suggests someone raised to believe that excellence would eventually meet intention. When she enters the process with a long-held crush on Ed—a boxer she admired from her past—the moment feels almost cinematic. There is history there, admiration, and patience, as though timing and proximity might finally align the story in her favor.

What becomes increasingly clear, however, is that Nicole lacks something modern dating quietly demands: strategy. Not manipulation, but an understanding of how men respond to pacing, intrigue, and ego. Nicole does not know how to flirt in a way that withholds just enough to create pursuit. She does not tease interest or lead with ambiguity. Instead, she shows up candid and emotionally transparent, offering honesty, vulnerability, and clarity—the very qualities men often claim they want when asked to describe their ideal partner.

Yet standing beside women like Dominique, a fashion stylist who understands how to balance allure and distance, or Lauren, whose presence commands attention without explanation, or even her friend Ashante, who instinctively knows how to spark curiosity and keep men slightly off balance, Nicole’s approach falters. Not because she is lacking, but because she is playing the game fairly in a system that does not reward fairness. No one taught her that when it comes to men, ego is often the first point of connection, and that enthusiasm for partnership—especially early—can be misread as availability rather than value. Nicole’s mistake is not that she wants to be a wife. It is that she believes wanting it openly should work.

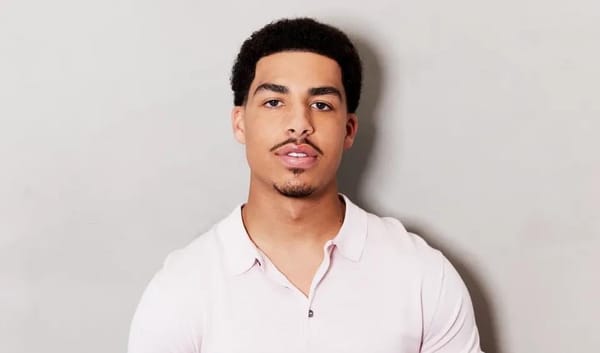

Channon’s experience mirrors this truth in a different register. A highly accomplished medical professional, Channon carries herself with old-school polish and propriety. She is Jack-and-Jill coded, pearl-wearing, impeccably spoken, and deeply rooted in respectability. She embodies the kind of woman who was taught that standards are protection, that breeding and boundaries would naturally position her as the prize.

Channon introduces her standards clearly, confidently, and without apology. Yet instead of being received as a woman to pursue, she is often treated as a woman to postpone. The men do not reject her outright; they simply relegate her to the category of “later”—the kind of woman one settles down with after exploration, after curiosity, after indulgence. While the audience watches, bewildered, recognizing Channon and Nicole as ideal partners to build a home with, raise children with, and grow old alongside, the men gravitate toward women who offer more immediate stimulation, novelty, or ego reinforcement.

This is where Jazmine Sullivan’s warning cuts deepest.

A Girl Like Me is not about bitterness—it is about disillusionment. It questions why women are taught to suppress appetite, delay desire, and perfect respectability while men are allowed curiosity, experimentation, and contradiction. Nicole and Channon did not fail at dating; they believed in a doctrine that no longer governs the market. They trusted that discipline would translate into desire, that readiness would be recognized as value, and that goodness would eventually be rewarded.

Instead, Ready to Love exposes a cultural misalignment. Men are not always choosing safety or suitability; they are responding to how a woman makes them feel in the moment. Chemistry, intrigue, and affirmation often outweigh credentials and character early on. In that environment, good girls are not rejected—they are deferred.

The tragedy is not that Nicole and Channon struggle to be chosen. The tragedy is that so many women like them were taught that being chosen was the inevitable outcome of doing everything right. Jazmine Sullivan was not telling women to abandon their values; she was warning them not to confuse virtue with leverage. Being a good girl is still honorable. It is still worthy. But it is no longer insurance.

Ready to Love airs Fridays at 8 p.m. EST on OWN, and beneath the romance and reality-TV spectacle, it offers a sobering mirror. For women who see themselves in Nicole and Channon, A Girl Like Me does not sound like a song—it sounds like a truth arriving late, but right on time.